The Japanese embassy to Ethiopia in collaboration with Japan International Corporation Agency (JICA) shares a postwar economy recovery alongside their development goal and high growth approach with Ethiopia.

The event which had sensational bounce back strategies was held in the premises of Addis Ababa University 6kilo campus on 19, 2022 with the attendance of Amb. Ito Takako, JICA staffs, members of the African Union Commission, lecturers of AAU and students.

In her opening remark Amb. Ito Takako explained that Japan is ready to share its experience with Ethiopia and will continue assisting the latter to achieve growth and prosperity.

Presenting a lecture entitled ‘Japan’s Postwar Recovery and High Growth 1946-1970’, Prof. Kenichi Ohno from Japanese National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) said that, Ethiopia can draw important lessons from Japan to meet development goals and record economic recovery after the pressing times.

Japan embassy shares post war economy bounce back

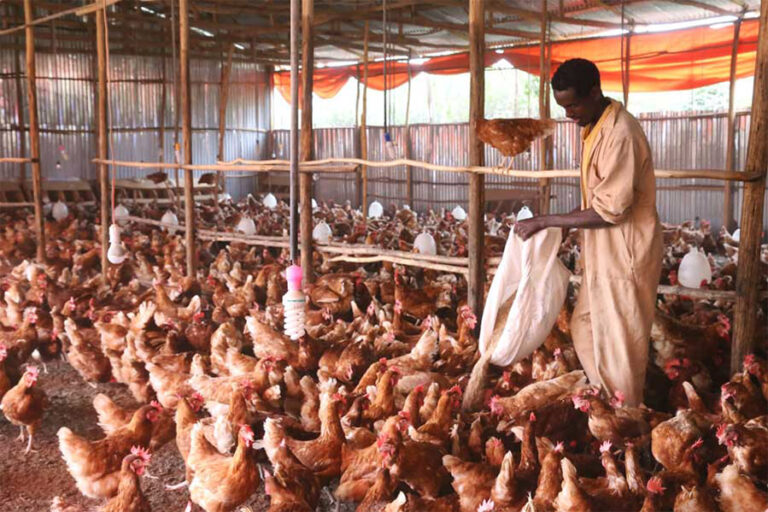

Sustainable energy proves pivotal for poultry farming

New study reveals lack of sustainable energy as the major challenge to smallholder poultry farming which accounts to almost all of the chicken production in Ethiopia.

The report conducted by Precise Consults Ethiopia Market Accelerator Programme (EMA), Selco Foundation, and Selco Foundations initiative Global SDG 7 Hubs, under the theme, ‘empowering smallholder poultry production through renewable energy: challenges and the way forward’ identified and presented three critical energy-related challenges that obstruct the overall poultry welfare and productivity of smallholder farmers in Ethiopia.

The first to be noted was the ineffective incubation process, caused by an inconsistent supply of electricity, which causes the DOC supply to decrease, making some smallholder farmers idle for up to 7 months. The second was poor lighting and heating in poultry sheds during brooding, also caused by lack of electricity. This has caused low productivity in smallholders’ poultry products as it directly affects feed intake, growth, and meat yield. The lack of cold chain storage is another crucial energy-related challenge that affects vaccine effectiveness, leading to the high mortality of chickens. This has also affected smallholder farmers’ ability to regulate their chicken meat supply as they cannot store slaughtered meat.

The assessment which focused on small-scale intensive farmers or backyard poultry farmers stated that renewable and off-grid source of energy as alternative solutions which will go a long way to reducing the sector challenge.

“Implementing renewable energy solutions in the poultry value chain enables smallholder farmers to address their challenges in accessing high-quality day old chicks and vaccines and helps them acquire better yields of meat and eggs,” the report explained.

“Solar appliances can help poultry farmers overcome these critical challenges and increase efficiency and productivity. Solar incubators increase egg productivity and ensure a better hatchability rate by minimizing the side effects of unreliable power supply,” the report said.

It added that providing adequate solar lighting can improve feed intake at night and maximize egg production in layer chickens, “moreover, providing sufficient heat in poultry sheds decreases chick mortality.”

According to the report, it improves feed conversion rate by encouraging growing chickens to use consumed feed to gain weight instead of maintaining a constant body temperature.

The report also identified that solar refrigerators can be used to ensure vaccine effectiveness and unlock the potential of engaging in value-adding processing activities for smallholder farmers.

It revealed that based on the assessment, solar energy interventions that can have a high impact on smallholder poultry farmers include solar egg incubators, solar lighting and heating systems for brooding, and solar cold storage systems to ensure the quality of inputs and poultry products.

Regarding access to the solution and the technology the assessment stated that there are challenges.

The report explained solar companies in Ethiopia have been partnering with microfinance institutions to provide loans to end-users to make solar home systems affordable to the farmers. However, the high collateral requirements to acquire the loans and the short repayment periods are challenges these farmers face. Poultry farmers also face challenges accessing loans to purchase the inputs needed to sustain their farms.

Small scale poultry farmers comprise about 97 percent of the poultry producers in Ethiopia, where rearing poultry provides a source of income and ensures food and job security for these farmers. Also, the regional states of Oromia, Amhara, SNNP, and Tigray account for 96 percent of the chicken population in Ethiopia.

Agricultural machinery, 1st Q dips but market remains strong

The first three months of the year show a decline in sales of agricultural machinery compared to the same period in 2021. The market contraction is organic compared to the record levels reached in the first quarter of last year. Incentives continue to support the market but geopolitical uncertainties may weigh on the coming months

The machinery market held up well in the first quarter of the year, albeit with a drop compared to the record volumes reached in the same period of 2021. Registration figures, processed by FederUnacoma on the basis of registrations provided by the Ministry of Transport, indicate a total of approximately 5,400 units sold for tractors, down 9.9% compared to the first quarter of last year when registrations were up 57.6% on 2020.

In the first three months of 2022, sales of combine harvesters reached 41 units, down 26.8% compared to the previous year (in the first quarter of 2021 they had grown by 180% compared to 2020), while registrations of tractors with loading platforms reached 132 vehicles, down 10.2% compared to the first three months of 2021 (+21.5% compared to 2020). Trailers and telehandlers also remained at high levels, closing the first part of the year with 1,944 (-8.2%) and 309 (-18.7%) units sold, respectively. Also for these two types of machines, the drop in 2022 has a relative weight, as it refers to a quarter that in 2021 had seen record increases in registrations (compared to 2020: +37.4% for trailers, +86.3% for telehandlers).

After a 2021 marked by extraordinarily high sales volumes for the agricultural machinery market, the setback observed from January to March can therefore be considered organic, as demand for agricultural technology continues to be strong. The transition towards agriculture 4.0, with investments for the purchase of the latest generation of mechanical equipment, and the simultaneous presence of several financing instruments for the purchase of agricultural machinery (credit for 4.0, Nuova Sabatini, NRRP, PSR, Bando ISI-Inail) contribute to supporting this demand. However, as the year progresses, sales trends will inevitably be affected by very significant economic factors.

“We find ourselves in a contradictory economic phase since, while the demand for machinery is going well, price volatility and difficulties in the supply of raw materials, which have been greatly exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, are threatening market growth,” explains Alessandro Malavolti, president of FederUnacoma.

The commodity emergency is not only affecting the agricultural machinery industry, making production processes much more expensive, but is also affecting the agricultural sector which, driven by a generalised increase in costs (especially those relating to energy and fertilisers), is seeing its own investment capacities decline. “In this scenario it is necessary to combine very short-term strategies with a long-term strategic vision, also aimed at exploring new channels and supply methods for raw materials,” sensitized Malavolti.

Production tests kick start at Aluto Langano

Ethiopian Electric Power (EEP) announces that production tests on drilled Aluto Langano Geothermal site has commenced.

The state owned electric power producer revealed that the power export has been cut by half starting from this week to keep sustainable power supply in relation to the two religious festivities.

The Aluto Langano, the only developed geothermal site in Ethiopia, which started its expansion work last May, has so far accomplished the drilling of four wells.

Moges Mekonnen, Public Relation Head at EEP, told Capital that the production tests of the four drilled wells will be commenced and that the testing that will be undertaken on two weeks interval. “The testing period may take three months,” Moges stated.

In total 12 wells will be drilled under the project that will be fully finalized at the end of the coming year. Currently, the fifth well is being drilled and the drilling of the sixth well commences soon. “The drilling work was commenced with delays owing to the water supply not flowing at the expected time which is crucial for the project,” the Public Relation Head explained.

The Kenyan firm, KenGen which has carried out the drilling works using two geothermal drilling rigs has allowed the project to run swiftly.

Located about 145km south of Addis Ababa on the Aluto volcanic complex in the main Ethiopian Rift Valley, Aluto-Langano is the only producing geothermal field in Ethiopia and experts express that it is probably the best studied prospect in the Ethiopian Rift. Geoscientific exploration began in 1973 and led to the siting of an exploration well LA3 on top of the volcanic complex.

The well was drilled in 1983 to a depth of 2, 144 meter. Since 1990, Aluto had produced electricity which has now been interrupted in connection with the expansion project.

The undergoing expansion that consumes USD 218 million with the major share being covered by the World Bank of IDA support through ‘Geothermal Sector Development Project’ plans to generate about 70 MW.

In related development, EEP disclosed that the power supply to Djibouti and Sudan has dropped by half starting from this week.

Moges said that EEP, which is responsible to generate and transport power up to the substation besides manage the energy export, to keep the local sustainable power supply in these holiday season has cut the export by half.

He said that the power supply to the two neighbors will continue after the end of the holidays.

He reminded that the peak hour for electric demand used to start at 6 pm, “however since the Ramadan season started the peak hour has come up to 3 pm.”

“Taking the growing power demand to consideration EEP has been undertaking massive preparation for the fasting season and two Christian and Muslim holidays to provided sustainable power,” he explained.

“As per the preparation, the team has been formed, and each unit at the generation plants, sub stations and transmission lines have been tested and made ready,” he added.

Optical fiber cables have also been tested.

A standby team has been formed and dispatched at stations and technical facilities to handle any interruption when it occurs.

“Grid stability stations like Gibe III and Tana Beles have also been specially tested since they are vital for restoration if any interruption occurred,” he said, adding, “as per our experience in similar holiday seasons in the past years, the power demand is from 2,500 to 2,600 MW but now me have made available up to 2,800 MW of power to mitigate the sudden demand.”

Besides the 2,800 MW ranges, EEP has provided a standby reserve if any additional demand shall be needed.

Since EEP is responsible to produce and provide electricity up to distribution stations; it has disclosed that it is working with Ethiopian Electric Service, energy retailer, to ensure sustainable power supply for the two holidays.